Soldiers may have cleared the sit-in, but they could not end the revolution. It shifted into courtyards and kitchens, back alleys and WhatsApp groups, where people reimagined survival itself as a political act. After the October 2021 military coup dissolved Sudan’s fragile transitional government, formal politics stalled, but the uprising’s social energy did not fade. Instead, it was redirected into a quieter, slower struggle to create new forms of life and governance from below.

Neighbourhood resistance committees (lijan al-muqawama), first organised to mobilise protests, became the backbone of this next phase. With ministries paralyzed and services collapsing, these committees coordinated food distribution, sourced medical supplies, arranged safe routes during crackdowns, and mediated local disputes. Their work embodied what sociologist Asef Bayat calls quiet encroachment—the patient, everyday expansion of autonomy by ordinary people. Rather than waiting for decrees or negotiating tables, they steadilyassumed the functions the functions of a state that had withdrawn, proving that authority could be rebuilt from the street level. As Bayat’s concept suggests, resistance in Sudan after 2021 was no longer about seizing power, but about quietly reclaiming the right to live with dignity.

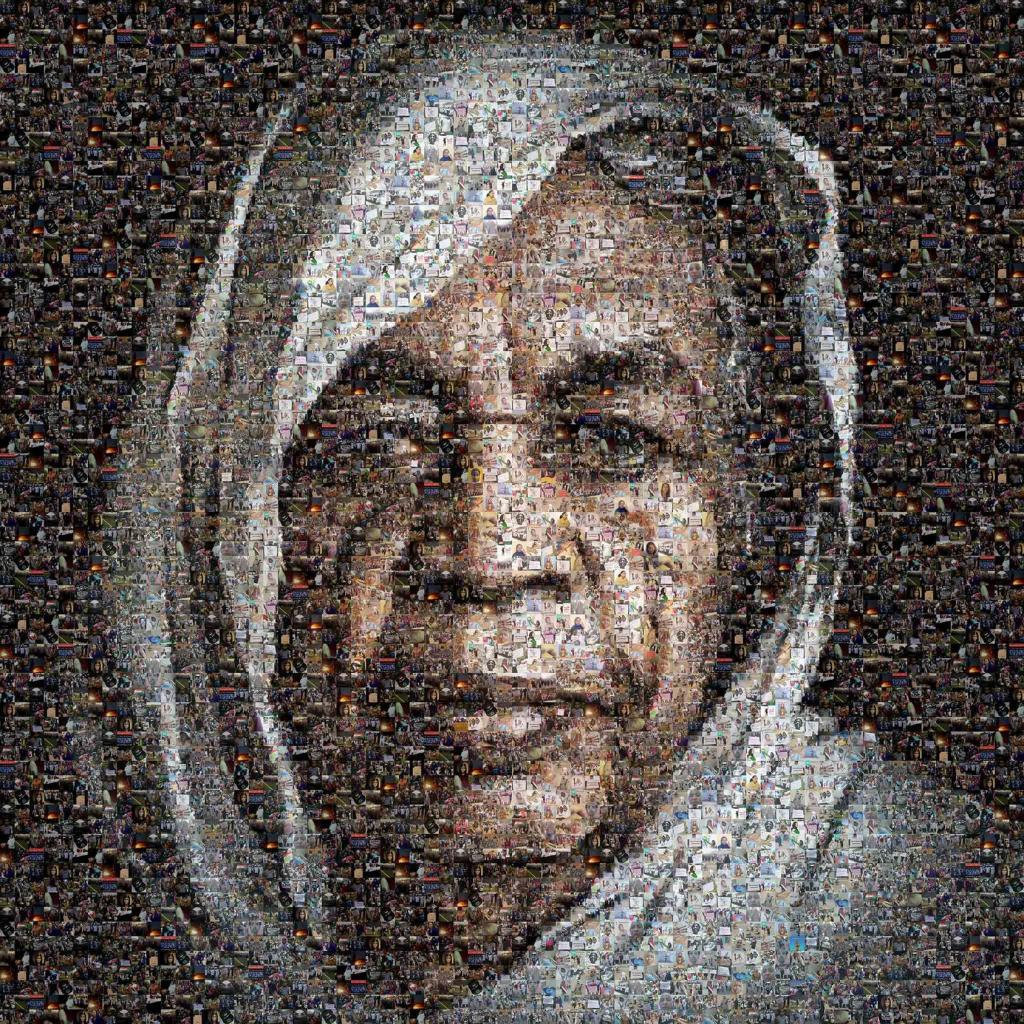

Women’s networks were central to this transformation. Long the custodians of Sudanese communal life, women converted their knowledge of household management into collective strategies of survival. These were not formal organisations or branded initiatives but spontaneous acts of solidarity: neighbours cooking together, mothers pooling medicine, young women coordinating safe passages through curfews. They organised communal kitchens, secured life-saving medicine, and opened their homes as spaces of shelter and deliberation. In doing so they enacted prefigurative politics living the democratic and egalitarian future they envisioned, not as a promise deferred but as a practice unfolding in the present. Their labour showed that care work, so often dismissed as private, is in fact political at its core.

Even when security forces made public gatherings dangerous, encrypted WhatsApp groups and other digital spaces kept collective decision-making alive. These networks extended the open, participatory ethos of the 2019 sit-in into everyday life, enabling dispersed communities to debate priorities and distribute scarce resources despite surveillance and repression.

By mid-2022, international headlines had largely moved on, framing Sudan’s revolution as broken. Yet within neighbourhoods across Khartoum, Atbara, and Port Sudan, a different story persisted. Through shared meals, mutual protection, and collective deliberation, Sudanese communities were proving that the revolution was not an event to be won or lost in a single day. It was, and remains, a long process of social reconstruction one that measures victory not only in the fall of rulers but in the patient work of remaking society from below.

References

Abbashar, Aida. Resistance Committees and Sudan’s Political Future. PeaceRep: The Peace and Conflict Resolution Evidence Platform, 2023.

https://peacerep.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Abbashar-2023-Sudan-Resistance-Committees.pdf

Bayat, Asef. Life as Politics: How Ordinary People Change the Middle East. 2nd ed. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2013.

Europe Solidaire. “Women in Sudan: Their Role, Their Rights, Their Resistance.” Europe Solidaire Sans Frontières, 2022.

https://www.europe-solidaire.org/spip.php?article62120

Scott, James C. Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985.

Sedig, Mayada. “Women and the Revolution: Feminist Organizing in Sudan’s Resistance.” Feminist Africa 5, no. 1 (2024).

https://feministafrica.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/04_FA-Vol.5.1_Feature-Article_Mayada_Sedig.pdf

Tønnessen, Liv. “Sudanese Women’s Revolution for Freedom, Dignity and Justice Continues.” Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI), March 2022.

https://www.cmi.no/publications/7355-sudanese-womens-revolution-for-freedom-dignity-and-justice-continues

The Timep Initiative for Policy. “Resistance Committees: The Specters Organizing Sudan’s Protests.” TIMEP, November 26, 2021.

https://timep.org/2021/11/26/resistance-committees-the-specters-organizing-sudans-protests/

Verjee, Aly. “Understanding Sudan’s Transition: The Role of Resistance Committees.” Forum for Development Studies47, no. 4 (2020): 511–529.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/1600910X.2020.1856161

Leave a comment