In a nation where the truth is a weapon of the powerful, where massacres are denied, archives are deliberately destroyed, and history is rewritten to serve the victors. The simple, defiant act of remembering becomes a radical form of resistance. For the people of Sudan, memory is not a passive looking back; it is a political act performed daily. It is how the revolution is kept alive, not as a lost dream, but as a persistent, guiding truth in the face of ongoing violence and displacement. The families who, in the midst of unimaginable grief, meticulously document the names and stories of their martyrs, ensuring they are not just a number in a news report but a life with a purpose. It is in the whispered recitations of the “martyrs’ list” at gatherings, a quiet act that reasserts the price of freedom and the promise owed to the martyrs.

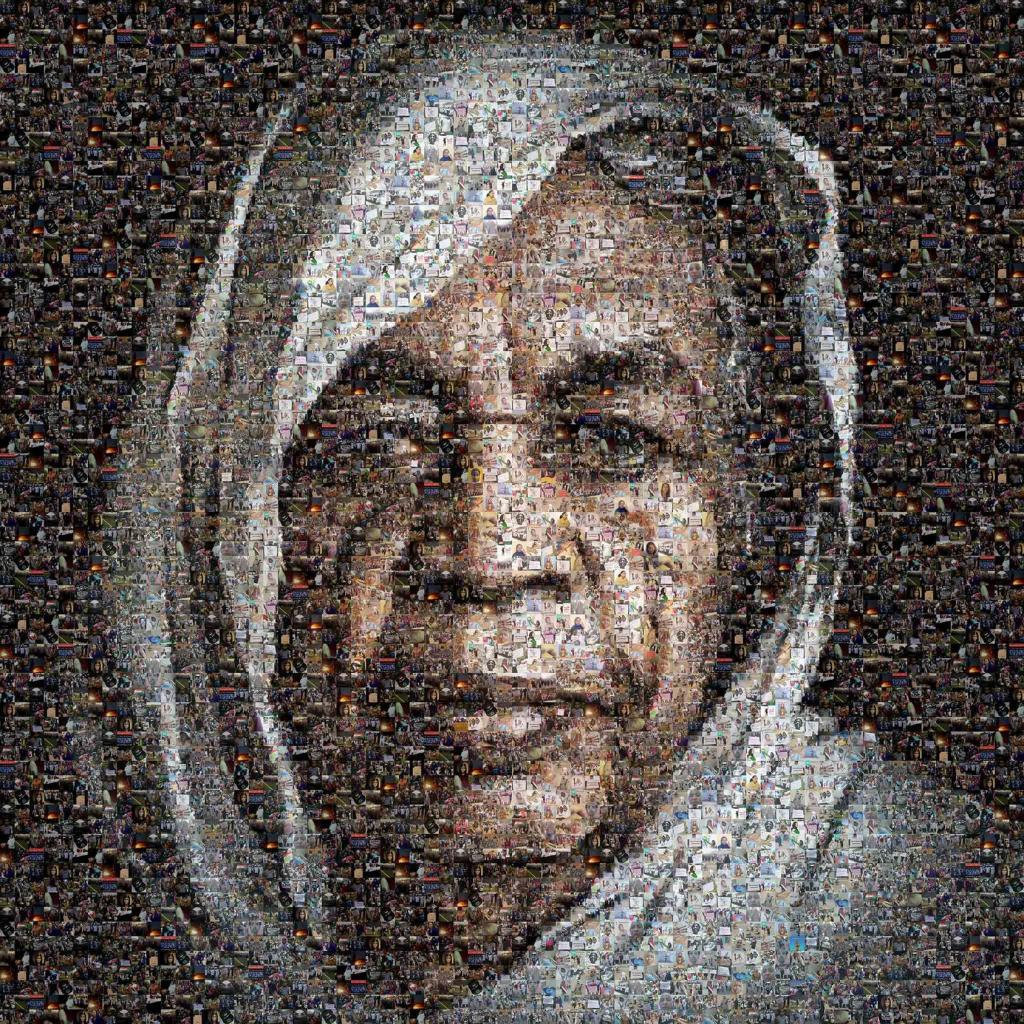

We see this act of remembrance on the walls of Khartoum itself, now scarred by war. Before the conflict, artists turned the city into a living canvas, painting the faces of the martyrs onto the very barriers erected to silence them. These murals were more than tributes; they were public claims on space and history, a way of saying “we were here, we are here, and we will not let you forget.” Even as these walls are bombed or painted over, their images live on, digitized and shared, a testament to their enduring power.

Now, with a war attempting to erase its own crimes, this work has become more urgent and perilous. A new generation of archivists, often working from exile collect and verify testimonies: a video of an airstrike, a photograph of a destroyed market, a voice note from a besieged city. They store this evidence on social media, building a digital testament for a future day of accountability. They understand that to control the past is to control the future, and they are fighting to seize that control back.

This work of memory is not done in isolation. It is a collective project that binds the diaspora to those who remain, the past to the present. The stories of the 2019 revolution fuel the solidarity networks of today, providing a map for how to organize, how to care for one another, and what to fight for. The memory of the sit-in’s communal spirit becomes a model for current mutual aid efforts.

Remembering is how the revolution’s blueprint is preserved.

Ultimately, to remember in Sudan is to act. It is to insist that the meaning of the revolution the demands for freedom, peace, and justice that transcends the counter-revolutionary violence meant to kill it. By weaving personal loss into collective history, Sudanese people are building a shield against erasure. They are ensuring that even if the state fails to record the truth, the people will. They are writing their own history, not in ink, but in action, ensuring that the past, with all its lessons and sacrifices, remains a living, active force in the struggle for the future.

حرام علينا لو دم الشهيد راح

Translation: “Shame on us if the martyr’s blood is forgotten.”

References

Aalen, Lovise. After the Uprising: Including Sudanese Youth. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI), 2020. https://www.cmi.no/publications/7420-after-the-uprising-including-sudanese-youth.

Freedom House. “Two Years of War in Sudan: From Revolution to Ruin and the Fight to Rise Again.” Freedom House, April 17, 2025. https://freedomhouse.org/article/two-years-war-sudan-revolution-ruin-and-fight-rise-again.

Ibreck, Rachel. “Counter-Archiving Migration: Tracing the Records of Protests.” International Political Sociology 18, no. 4 (2024). https://academic.oup.com/ips/article/18/4/olae035/7810806.

Sudan Art Archive. Sudan Art Archive. Accessed October 12, 2025. https://sudanartarchive.com.

Sudan Memory. Sudan Memory: Preserving Sudan’s Cultural Heritage. Accessed September 12, 2025. https://www.sudanmemory.org/?

The Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy (TIMEP). “Beyond the Battlefield: Sudan’s Virtual Propaganda Warzone.” The Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy (TIMEP), January 14, 2025. https://timep.org/2025/01/14/beyond-the-battlefield-sudans-virtual-propaganda-warzone/.

United Nations. “Sudan Conflict.” UN News, 2025. https://news.un.org/en/focus/sudan-conflict.

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). “Adolescent and Youth Participation.” UNICEF Sudan, 2024. https://www.unicef.org/sudan/topics/adolescent-and-youth-participation.

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). “Empowering Sudanese Youth: Pathways to Peace, Stability and Prosperity.” UNDP Sudan Blog, July 15, 2025. https://www.undp.org/sudan/blog/empowering-sudanese-youth-pathways-peace-stability-and-prosperity.